Minneapolis's reviews

Opera News August 2006

IN REVIEW

ST. PAUL — Joseph Merrick, the Elephant Man, Minnesota Opera, 13/05/06

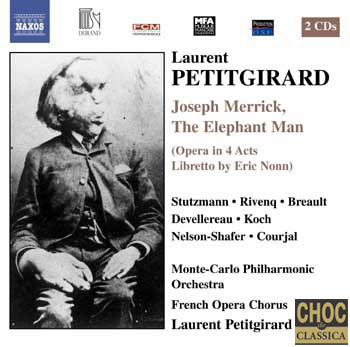

Bravo to Minnesota Opera for presenting the American premiere of Laurent Petitgirard's opera Joseph Merrick, the Elephant Man. With its haunting, poignant score and its provocative, skillfully woven libretto by Eric Nonn, Elephant Man has the distinct feeling of a modern classic. The story of the hideously deformed Englishman Joseph Merrick (1862–90), who spent the last years of his life in residence at London's Whitechapel Hospital, is familiar to many via Bernard Pomerance's Broadway play and David Lynch's 1980 film. Petitgirard and Nonn's richly composed realization of Merrick's life presents few obvious heroes or villains. Tom Norman, the sideshow presenter — sung impressively for Minnesota Opera by tenor Theodore Chletsos in a showy yet dignified performance — exploits Merrick's deformity for financial gain but offers him genuine kindness and respect (not to mention employment). In Christopher Schaldenbrand's compelling characterization, Dr. Treves — the physician who insists that Merrick be hospitalized for his own good — is initially insensitive to Merrick's human side, maintaining a clinical focus on his condition. Later, a newly empathetic Treves manages to convince Carr-Gomm, the stern, budget-minded hospital director (sung with powerful resonance by bass-baritone Seth Keeton) to run a newspaper ad appealing for charity on Merrick's behalf.

Merrick himself was sung rivetingly by countertenor David Walker, whose every unearthly utterance transcended his abject circumstances. (Petitgirard composed the role for contralto voice but told this writer that Walker's versatility of timbre and communicative power won him over.)

Merrick's high-society patrons are depicted as far more monstrous than he. This point was driven home magnificently by La Colorature, who showed up in full diva regalia and delivered a freakish, impossibly high virtuoso aria, oscillating maniacally across the interval of a minor seventh. Soprano Mary Wilson giddily knocked off this terrifying number as if she were having the time of her life. This was a perfect contrast to Alison Bates's vocally vibrant yet emotionally understated portrayal of Mary, Merrick's affectionate nurse.

For this production, Doug Varone, the director and choreographer, enlisted his eight-member troupe, Doug Varone and Dancers, to provide an ongoing silent, visual dialogue with Walker's Merrick. The dancers created a mood-establishing pantomime in the opening moments of the opera, turned the entr'acte into a lilting ballet and added texture to certain scenes with nothing more than a graceful entrance.

Varone's decision to abandon any disfiguring makeup to portray Merrick's deformity — a device similar to that used in the original Broadway production of the Pomerance play — seemed questionable at first. By not having to confront extreme physical ugliness, the audience was let off the hook, in one sense: we could easily see Merrick's inner beauty — why couldn't everyone else? As the opera progressed, however, and the focus remained on Merrick's interior life, as embellished by his interactions with the dancers, Walker's physical embodiment, with his long mane of brown hair and limping gait, emerged as the right choice.

Petitgirard's lush, enveloping melodies (at least four of which I could walk out humming) are based mostly on the octatonic scale, a series of alternating whole and half-steps that forms an eight-note scale, as opposed to the seven-note scales of the standard major and minor modes. The result echoes Petitgirard's great predecessors Ravel and Poulenc, and the sumptuous chorale-prayer for the patients at the hospital is a not-too-distant cousin of Fauré's "Pavane" (and just as gorgeous). Varone's choreography made its most profound impact here, as the dancers, with consummate balletic grace, find themselves alternately drawn to and repelled by Walker's Merrick. This is a breathtaking scene — profound and universal — and at the end, one could have heard a pin drop in St. Paul's Ordway Center. The May 13 performance, expertly conducted by Antony Walker, had an impressive level of polish and ensemble for the opening night of a challenging new work.

JOSHUA ROSENBLUM

Return to the previous page